Pivoting to Trust - The Road from Service to Product

Understanding IT's historical roots as an internal service organization is key when considering a pivot to a Trust Product strategy. Because of this history, Information Security organizations are most often run as service organizations owing to their position in the org chart as an IT role. However, as pivoting to Trust requires a shift away from the ‘internal service’ organization model to the ‘product’ organization model, it is key to reframe the approach to the work and maximize the benefit of the Trust pivot. The shift from a service to a product mindset has been extensively documented in hundreds of business books (“Lost and Founder” by Rand Finch is a great starting point), and an understanding of the pitfalls of that shift will benefit the reader and enrich their understanding of the journey ahead.

The author has spent the last ten years designing, testing, and measuring the Value impact of various tactical and operational playbooks in the business software companies that he was committed to defending. During that time, he treated these playbooks as totality of a strategy he had taken to calling “Value Assurance” and invested in teaching other leaders and practitioners about its benefits. But once the Value Assurance playbooks were shown to deliver the predicted results, some basic questions remained unanswered: When and Why would an organization deploy this strategy? How do you operationalize it? What roles are necessary to execute the strategy and what are their objectives?

| IT Org | Trust Org | |

| Type | Service Org | Product Org |

| ROI Metrics | Service Metrics | Go-To-Market Metrics |

| Business Motion | Trailing Motion | Co-Motion |

| Alignment | Ops | Value |

| Peers | Ops | Revenue |

| Customers | Internal | Market |

Value Assurance at that stage of development was primarily a communications and organizational strategy that aligned previously unaligned business functions in a common service of Value. It provided a way to reframe Information Security as a G2M actor in the Revenue journey. What it didn’t tell us was why we would select the Value Assurance strategy in the first place, how to measure operational impact to revenue motions, or even what constitutes a “good” measurement: what business conditions or triggers must exist for us to consider this strategy over other strategies? How do we move a service organization to a product mindset? It became apparent that the Value Assurance strategy itself was only one layer of a multi-layer paradigm shift resulting from an interrogation of long-settled fundamentals to find a more effective strategy to influence the business.

An analysis was conducted to determine the nature of modern IT Security service organizations and the challenges they might face in moving towards a Trust product model. An analysis of 30 data-native organizations and how their technical service organizations were aligned to mission reveals four general classes of service shops: the Nothing Shop, the IT-Only Shop, the Compliance Shop, and the IT-Sec Shop (collectively, the “Four Shop Model”). Applying the RUN/DO Trust Product approach to the Four Shop Model produced this analysis of how various paradigms and practice models can evolve into an Assurance practice that moves in co-motion with the Business in the service of Revenue and Value. Pivoting to Trust requires an assessment of the current service practice across six dimensions: Paradigm, Practice, Strategy, Tactics, Operations, & Deliverable. Only through understanding the natural evolution, synergies, missions, and constraints of the Four Shops can a path to Trust be charted.

The Nothing Shop

| Shop Type | Nothing |

| Paradigm | Self-Defense |

| Practice | Cost |

| Strategy | Thoughts and Prayers |

| Tactics | Self-Sharpening Knife |

| Operations | Deliverable-focus |

| Deliverable | Variables |

A Nothing Shop has no formal approach to data operations, much of which is left to individual data practitioners. In a Nothing Shop, the paradigm is “self-tool, self-train, and self-defence”: there might be a process here or there, or a standard some align to, but for the most part the practitioners rely on whatever skill, tool, or knowledge they possess at go-time. A Nothing Shop runs within a cost-containment paradigm driving a Thoughts & Prayers strategy. “I hope we don't get hacked,” is the unspoken strategy, “we hope that nothing happens, and if it does, we have insurance”. A Thoughts & Prayers strategy inevitably leads to a tactical Self-Sharpening Knife approach, where practitioners are expected to be “tools that sharpen themselves”: run their own IT, figure out their own tools, and defend themselves however they can.

Reactive operations rule the day. If the deliverable is delivered, then "everything worked" and the tactic is not likely to be revisited or revised. The company, through its lack of investment, cannot properly support their practitioners ("sharpen its own tools") and instead relies on individual incentive, good fortune, and sound decision-making at scale to keep operations going (the "self-sharpening knife"). Operations are generally uneven but "good enough" for the business at hand, especially since the only metric is the existence of the deliverable at a certain quality whenever it is required. But those deliverables vary in quality (or existence) since the ecosystem in which they are crafted is unreliable, unsafe, uncontrolled, and generally under-measured. When business conditions push a Nothing Shop to evolve past this stage of maturity, they usually become IT-Only Shops.

The IT-Only Shop

Since the emergence of Information Technology (IT) as a business function in the 1950s, it has primarily acted as an internal service organization providing internal services for internal customers. In the 1964 book “The Automation of Business”, John Diebold discussed how IT could be used to automate many business functions…to increase efficiency. When large organizations began to centralize their IT departments in the 1970s, those IT departments provided internal business services such as data processing, computer operations, and software development (Gasser & Trauth, 2001). A survey by The Economist Intelligence Unit found that “two-thirds of the respondents saw IT primarily as a provider of services for internal customers” (Lacity & Hirschheim, 2004), while a 2002 survey conducted by McKinsey & Company found that “the majority…viewed IT primarily as an enabler of internal operations and customer service” (Koch & Schulze, 2002). This trend has continued into the modern era as a 2015 survey of over 500 global organizations conducted by Gartner found that “80 percent [of respondents] view IT as an internal service provider” (Gartner Research, 2015), while a 2017 study by the European Commission found that “81% [of respondents] see IT as a provider of services to internal customers” (European Commission, 2017).

| Shop Type | IT-Only |

| Paradigm | Service Delivery |

| Practice | IT Service |

| Strategy | Business Enablement |

| Tactics | Standards & Support |

| Operations | IT-Ops |

| Deliverable | Available Toolset |

IT Only Shops have always followed the business, moving in a trailing motion rather than co-motion because IT serves the Business within the Service Delivery paradigm as an IT Service practice implementing a Business Enablement strategy. IT-Only Shops engage and support their businesses through Standards and Support programs, with “business-class data operations capabilities” as the deliverable. Through normalized, governed, and aligned data operations, the Business gains the benefits of standardized service delivery and metrics that provide a predictable level of service availability, predictability, and performance. Most importantly, the IT-Only Shop budget sits squarely in the Operations budget. Any metrics an IT-Only Shop produces will be trailing and naturally unaligned to the Revenue strategy (such as service availability metrics, IT operations metrics, uptime SLAs, cost metrics and other Service organization metrics). The Business might use these metrics to determine if IT ROI is acceptable, if capabilities align to the G2M plan, or if additional capability is required to support the value journey.

The IT-SEC and Compliance Shops

Many organizations evolve past the IT-Only Shop model into two types of specialized IT Shops: the IT Security (IT-SEC) shop and the Compliance shop, both of which are analyzed here.

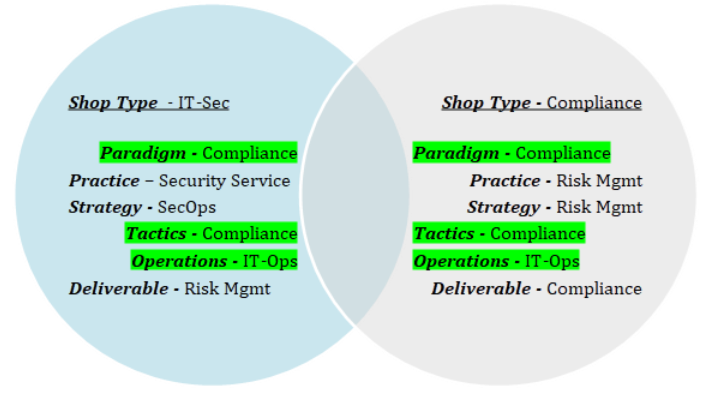

A Compliance Shop type is the more familiar of the two models due to its ubiquity in every regulated organization, where compliance operations are built into the areas of the Business impacted by compliance requirements. In the Compliance paradigm, compliance is a necessary aspect of business operations as non-compliance could be an existential threat to revenue or value; many service departments (such as IT, IT Security, and Finance) can operate under this paradigm. As such, the Compliance paradigm drives a Risk Management practice that manages risk according to mostly external compliance criteria. The Business ingrains in its workforce the importance of compliance to the revenue and customer journeys and designs compliant business processes that can withstand audit scrutiny. The ideal result of a Risk Management practice in a Compliance paradigm is Compliant Operations, which are typically seen by the Business as a baseline condition necessary to enable the G2M motion. In this paradigm, Compliance primarily serves the Business as a service organization responsible for satisfying regulatory, statutory, contractual, and insurance requirements necessary to keep the doors open and manage risk to an acceptable level. While “being compliant” is often understood by stakeholders as “crime resistant”, a review of the top twenty data breaches between 2014-2022 found that 25% of breached organizations were compliant with their contractual and regulatory requirements around Information Security and Privacy and yet were still victimized by cybercriminals. In other words, a focus on compliance lowers the risk of cybercrime...to a point.

An IT-Sec Shop has many similarities to a Compliance Shop, such as both working in a Compliance paradigm and being Operations functions with heavy technology focus, they diverge in mission from “compliance to keep the bus going” to “compliance to stop crime, improve safety, and defend value”. As an internal Security Services practice, IT-Sec Shops may have broader mandate than a Compliance shop and can apply more sophisticated threat models and methods, employing threat hunting, bug bounties, cross-functional app-sec, red teaming, and other value defense activities. IT-Sec Shops enforce compliance to security standards for all data at-rest and in motion and for all internal and external systems where scoped data assets are processed, whether an external compliance criterion requires it. Where a Compliance shop may view security investments above what is necessary for compliance as an operational cost, an IT Security shop may view the same investment according to asset value or business strategy and such investments are treated as what they are: value enablers. A Compliance Shop may contain a scoped IT-Sec Shop, or an IT-Sec Shop can evolve from an IT-Only Shop; in both cases, a well-run IT-Sec Shop can deliver more than mere compliance: it can deliver real security for the organization they exclusively defend.

The RUN/DO Shop and the Trust Product Practice

| Shop Type | RUN/DO |

| Paradigm | Stakeholder Safety |

| Practice | Trust Product |

| Strategy | Value Assurance |

| Tactics | Value Defense |

| Operations | 8 Business Drivers |

| Deliverable | Trust Story |

Where the Business recognizes that Trust is an essential component of the customer and revenue journey, it may decide to appoint a leader to own that Trust journey and its impact on Revenue and Value. In such contexts, the RUN/DO model elevates an IT-Sec or Compliance Shop to ownership of the Trust journey and its impact on Value by delivering a “trust product” to its Trust Stakeholders, the broader concept of market stakeholder upside. Combining the IT-Sec shop’s focus on core Information Security with the external validation focus of a Compliance shop creates the conditions for the establishment of a “trust factory”: interconnected, interdisciplinary, and cross-functional processes and procedures that generate prima facie evidence of Safety resulting from a scoped data processing motion. Within the Stakeholder Safety paradigm, Trust in multi-stakeholder assets is communicated through evidence of Safety compiled and communicated as a Story: Safety stories compiled into Security Stories, which are aggregated into G2M Trust Stories and consumed by Trust Stakeholders in a Revenue motion. This paradigm aligns to the broader Four Factors of Trust model driving value in the world's largest data-native organizations.

The Stakeholder Safety paradigm aligns to the broader Value journey and serves the incentive of the value stakeholders according to the duties bound to each value asset. Duties are Trust criterion in the Revenue journey which flow legal, regulation, insurance, contractual, compliance, and customer/market commitments down to the organization (and further downstream) that must be satisfied to accelerate the Value journey for all value stakeholders. The term “safety” is used to indicate a broader scope of defense: while “security” may focus on preventing unauthorized access, use, modification, or destruction of assets or systems, a “safety” focus prioritizes prevention of harm-to-value for all value stakeholders (as well as all other Security concerns). Within the Stakeholder Safety paradigm, the data protection leader acts as a soft data fiduciary, representing the value and interests of the data itself on behalf of all actors with a value stake in the safety of the data and the companies which process it. A safe company is a more valuable company, and focusing on building and communicating Trust increases revenue velocity, equity valuation, and account upside.

The Trust Product practice aligns participants around clean and repeatable evidence of safety in dataflows, net-flows, data stores, processing stacks, applications, services, touchpoints, and integrations. Whenever a value asset undergoes a state-change event, evidence of safety is collected under the EvidenceOps program which collects and transforms event data into security stories to support Trust artefacts delivered to market. Trust artefacts are forward-deployed communications assets which providing evidence of compliance, security, capability, and/or safety to Trust Stakeholders; over sixty-five Trust artefacts were used in the G2M motion of a B2B SaaS company serving eleven Trust Stakeholders customers, and more may be necessary depending on the nature of Trust in the Customer or Revenue journeys. The effectiveness of the Trust Product practice is powered by the Value Assurance strategy, which enables data protection leaders to quantify how Security Action X leads to Revenue Impact Z or how Safety Motion 1 leads to Value Influence 2 in metrics the Business cares about. By clearly drawing a line between Assurance and Revenue motion and enlisting other Value Storytellers (such as the CFO, GC, CIO, and P&C leader) to share the language of Value with their teams, a cross-functional value defense organisation can be established in service of the Revenue strategy.

Being safety-driven, a Trust Culture rewards people when they safely operate the machines which transform data into value. Tactical value defense can be reframed as a story about factories. Since industrialization, there have existed factories with machines (of varying safety and complexity) requiring human operators. The owner of the factory could walk around and see their machines working, with a factory widget being a real object that can be easily evaluated for quality and value. They could observe the operator running the machine. Operators were typically apprenticed into their role, where they could learn to safely operate the machines under a senior operator. Continuing the factory analogy, consider a common InfoSec activity such as security awareness training and how it’s done at most organizations. We remove knowledge workers from the line, teach them in a simulation, then place them back on the line to execute the new mental motion…instead of going to the line, watching the knowledge worker in motion, and bringing in-motion process safety to their work in their own context. Bringing safety to the knowledge worker is a core tactic of value defense, where all security tooling is refocused on user and data safety.

Because InfoSec motion is now Revenue motion, operations are guided by the Eight Assurance Business Drivers: reasons to “do security” that have little to do with safety and everything to do with Revenue. These eight drivers benefit from the consolidation the Corporate Security, Product Security, Application Security, Business Resilience, Privacy Operations, and Compliance Assurance functions (as well as certain functions of Legal, Procurement, and People & Culture) under an “Assurance Department” for the efficient governance of data, system, and user safety and value. The Assurance Department is a product practice disguised as a service practice, a quality program disguised as a defense program, and an active contributor to the organisation’s value story where Trust is material to Revenue. Data protection leaders should consider evaluating the scope of Trust for their organizations, including identifying areas of Trust friction in the revenue, customer, and value journeys. Data protection leaders can also begin or deepen conversations with peer Trust Storytellers in their organizations, securing their processes in motion to produce evidence that rolls up to Trust. As each Storyteller begins to reliably produce evidence of safety in the areas relevant to the Trust story, safety processes disappear into the work itself (meeting all security and compliance requirements). Where the Business recognizes that Trust is an essential component of the customer and revenue journey, an Assurance organization delivering Trust to market may be an attractive strategy to support Trust-impacted go-to-market motions.

Share this

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

From Protection to Safety: The Paradigm Shift Data Protection Leaders Must Embrace

Inherited vs. Manufactured Trust